In Defense of Doing Things Badly

I do not consider myself good at producing 2D art. I can sculpt in physical media pretty well, and I know my way around painting a miniature to a level I consider baseline competency. Drawing, though, has always challenged me. I took a painting class in high school, which taught me a bit about reference and perspective. But despite years of doodling on the margins of just about every paper I’ve ever had in front of me during a meeting, my skills remain at a decidedly amateur level.

But sometimes, in the name of creative exploration for my games, I create 2D art. Frequently, a visual placeholder is useful to understanding how people will perceive or interact with a component. Sometimes a free-to-use stock element will do the job, but oftentimes, I need or simply want to make something much more specific. And I think the exercise of my creating these drawings (crudely) is worthwhile to my process and, ultimately, to the games I make. So let’s discuss some of my doodles, and how crude drawings helped me design Stonesaga!

Crystallizing Ideas

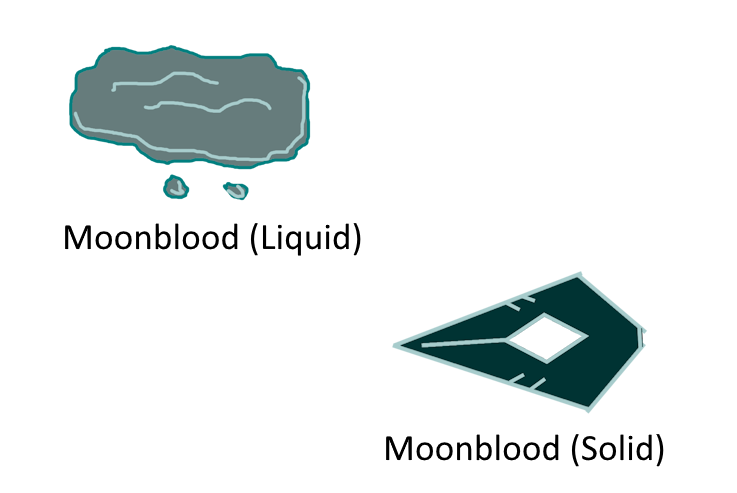

Early drafts of the moonblood material’s icons.

One surprisingly large part of my job, from when I began as an RPG producer at FFG to my latest projects, is the challenge of explaining what I want depicted visually. Writing a good art brief is a skill, and one I had to develop under the tutelage of my fellow producers and the company’s art directors. References, existing images that help you and the artist get on the same page conceptually, are vital to the process.

But Stonesaga presented a new challenge for me. Sure, I was good at finding the specific angle I needed of the T-65 X-Wing for an art brief depicting one zipping across the sky, and I knew how to communicate my ideas clearly in writing. But what about when I was describing something I had never seen before, let alone anyone else? Often, I knew what I needed mechanically (a rare material that starts as an unusable amorphous liquid but crystalizes to a sharp object under special conditions), yet didn’t have a clear mental picture of what this should be.

During the process of designing Stonesaga, I doodled a lot more than I had before. As I dug back into my files to write this article, I was actually surprised how many pieces I created - many of which never don’t correspond to anything that appears in the final game. However, looking back through these sketches, I can also trace the evolution of my ideas. Andrea Koroveshi’s final take on moonblood is much nicer than my crude draft. However, drawing out the prototype token for Luke helped us work out the way it functioned in the crafting system, and also helped articulate what was needed from the final art (and Andrea then knocked it out of the park, as usual).

Dreams in Fire

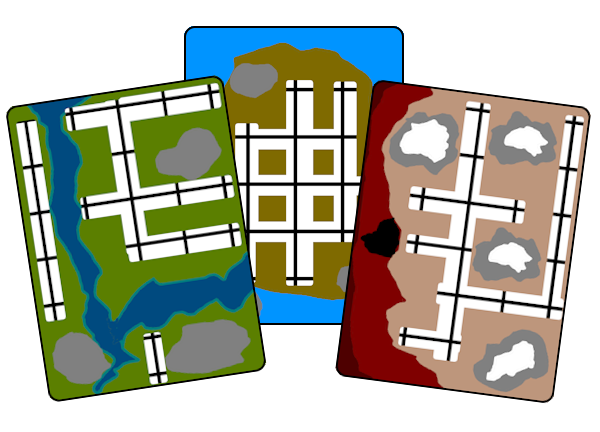

Early draft of a Delving card depicting an encounter with an underground beast!

Delving went through a number of design iterations, but in one version, the deck had a number of cards I referred to as “jumpscares.” Instead of having text, these cards would simply have an illustration. And sitting down one day, thinking about Andrea’s sketches of the above-ground predator, I started doodling what I thought its subterranean equivalent might be.

Early testing revealed that this was confusing, but putting text on the card was tricky without ruining the visual effect. Further, while it was a fun idea, it didn’t necessarily justify itself in an activity that was otherwise trying to emulate a classic choose-your-own adventure book. Ultimately, I dropped the plan for an art piece here.

Yet, I couldn’t stop thinking about these giant, carnivorous cave worms. The idea caught. Their sharp scales and ravenous appetites. And that had, shall we say, an impact on the game. I won’t spoil anything here, but sometimes, while you play, think about those cave worms. Rustling in the dark below. Always there, in lightless passages, listening to the drumming of feet.

Visualization and Selection

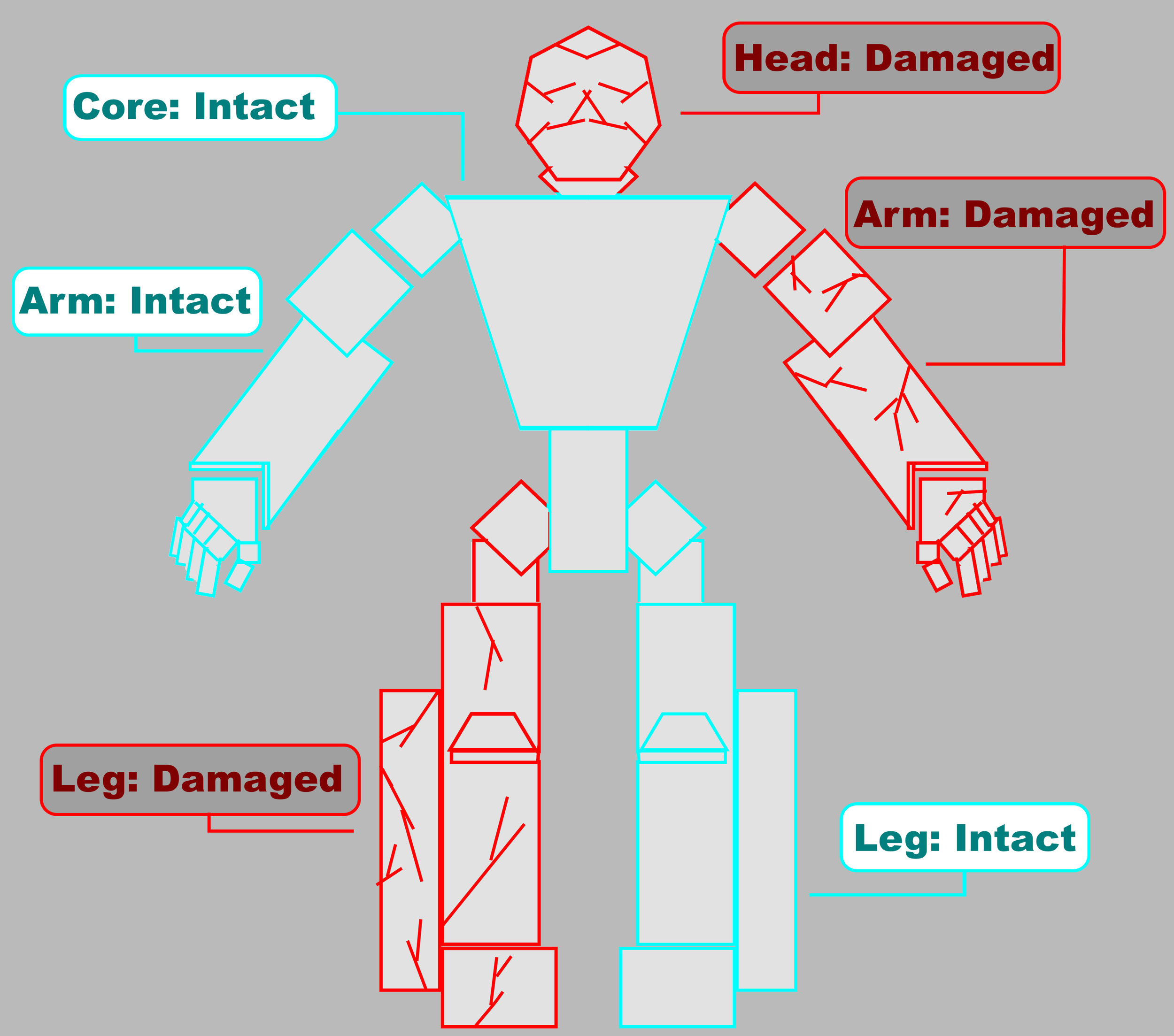

A concept sketch for village cards. It did not progress much further than this sketch.

Sometimes, just prototyping something can allow you to decide you don’t like it. Early in the game’s development, Brendan and I juggled a number of concepts for village-building in Stonesaga, before settling on the simple-but-effective rules for outposts. One of these concepts was village cards, cards with slots to accommodate standees or some other physical representation of buildings. As an unformed and nebulous thing, I felt the idea could work and I liked some of what it had to offer, so Brendan asked me to come back with a prototype.

I spent an afternoon on several concepts sketches, including the one shown above. I worked through the angles on the screen in front of me, and the effort of doing so revealed to me that the concept was just too fiddly. Drawing these gave me the proverbial lay of the land in a way asking someone else to draft something couldn’t.

Perhaps more importantly, this process also helped to show the lower bounds of the concept. To work, the concept needed to be intuitive. If I could find a way to make it work with my crude sketches backing it up, it would certainly be possible for an experienced artist and graphic designer to execute it in a simple, clear way. That didn’t happen, and that gave the the clarity I needed to see that the idea, while conceptually intriguing, wasn’t going to gel.

The Future

Foreshadowing?

Why is this top of mind? Well, besides the fact that I want to illuminate a bit more of my creative process as Stonesaga’s release draws close, there’s a conversation that has been bubbling for a while in the games community (predominantly digital games). Generative image models are become increasingly refined and, perhaps more significantly, much more deeply integrated into tools many people already use. And a large part of the overt appeal of these systems, I believe, is an implied promise: “You never need to be bad at [insert thing the machine purports to do] again.”

So what I wanted to explore was my own relationship with the things I “do badly” during my own creative process. Are these crude sketches useful? Do they enhance the product even if they will never be sufficiently refined for the final product? Are they worth my limited time?

As I’ve reflected above, I believe real, crucial things would be lost in my process if I never sketched another horrible little doodle. These explorations outside my area of skill and experience caused me to develop my ideas in ways that had far-reaching consequences across the game. They helped me to think from the perspective of others, improving my communication with the skilled artists who can actually make stuff look nice. They expanded my thought process, opening me up to new ideas I wouldn’t have considered in my usual medium of prose. And they gave me a chance to reflect on the quality of my ideas from a new angle as they passed the gauzy barrier between conceptual and concrete.

So I’m going to keep doodling, not terribly well (I clearly didn’t get the drawing skill in the family that my sister did) and I’m going to keep learning from it.