2025 in Game Design

Last year, I concluded a year of relative blog inactivity with a hint of things to come.

Oh foolish, foolish Early 2025 Max.

Self-indulgently, I peppered little hints into that article. Oh, I had such aspirations for 2025 in December of 2024! I had plans to announce the formation of my new game company in 2025! I had a new, exciting project that I’d be taking to crowdfunding within the confines of the year!

Well, it turns out things take time to cook, especially when you’ve already got pots on all the burners. Let’s talk about what I got up to while I was neglecting my design blog in 2025. Once again, I’ll boil each set of musings down to a question that I want to ask myself as I carry out future projects.

Slow Cooking

Selection from Morning, Claude Joseph Vernet, 1760. Courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

I’m thrilled that Stonesaga will, knock on wood rock, be in people’s hands very soon. To all the backers of the game, I immensely appreciate your patience! At the end of 2024, I was doing final internal file review. I knew there would be work extending into 2025, but one thing that I didn’t expect for 2025 was the sheer amount of Stonesaga work remained from a design perspective. The playtest is over finished, production is in process, so what could possibly be left?

Admittedly, both Brendan McCaskell and Andrew Fischer did both warn me that foreign partners would have extensive questions about a game as expansive as Stonesaga, and that addressing these would take time. And I’d gone through this on past projects like X-Wing 2nd Edition (though in that case, Frank Brooks handled the lion’s share of the workload).

What I was perhaps unprepared for was the emotional scale of the task. Encountering a huge list of highly specific questions about the game by professionals paid to understand it on an extremely deep level was exhausting in a way I just hadn’t understood. Encountering *five* such lists was… daunting.

Other than the playtest process, these partner questions made up the most rigorous interrogation of the game. In some areas, it was even more thorough than the playtest process. Playtesting, even mass or open playtests, tends not to expose all elements of the game to equal scrutiny. Certain paths are naturally more popular, be these especially exciting character builds, particular choices in linear story games, or certain story beats that are the most likely to occur in an emergent narrative game like Stonesaga. You can take some steps to get the most out of your playtesting (as I’ve discussed before). Still, players gravitate towards certain options, and those typically end up the most polished.

But translators aren’t approaching the game as players. They might play the game, but they spend most of their time digging into the text deeply instead. This casts certain aspects of it in much sharper relief. Enjoyment of the game isn’t part of the picture most of the time, so they aren’t attuned to questions of subjective “feel” for which playtesters are so indispensable (e.g. “Is the fishing activity fun?”). Because of that, translators don’t gravitate towards the most (or least) fun parts of the game and focus their feedback there. The upshot of this is that suddenly, just when you think you’re done, you’re getting questions you’ve never heard before, and often they’re really incisive questions. And then you’re digging through the drafts of your own game asking “Wait, is there an answer for this? Didn’t I account for it? I swear I did…” and questioning everything you remember writing. In the moment, that often felt overwhelming.

To be clear, Stonesaga is much better for this process, and I commend our partners for all their interrogations of the material. They really made Stonesaga a much better game. I just hadn’t fully absorbed the scope of the process, or how it would affect me. The question here is straightforward enough: What parts of this process do I know will require me to learn new skills or processes, and how can I intentionally leave aside extra time and emotional energy to grapple with them?

Keeping all the Burners Lit

A Medieval Bakery, courtesy the Met Museum. No clever caption, I just like medieval inset images and marginalia.

Meanwhile, other games I reported on in 2024’s post have been chugging along with new content for the future. WizKids’ Star Trek: Into the Unknown has expansions in the pipeline (Rising Tensions has recently become available, and Glory and Zeal recently announced). Brotherwise Games’ Cosmere RPG’s foray into the world of Scadrial has a release date, with the Mistborn RPG slated for fall of 2026.

Michael Gernes and I are still very involved in the day-to-day design of Star Trek: Into the Unknown. The game’s release cadence is more relaxed than other plastic spaceship games I’ve worked on, so we’ve had plenty of time to keep our thematic designs stewing for that extra bit of flavor. It also helps that we frontloaded a lot of design work in STIU. By setting out all the major factions and their mechanical identities in the game at the outset, we made later work much easier. We knew that both Klingons and Cardassians, for instance, would have a focus on offensive teams. While Klingon combat teams excel at daring raids and disruptive strikes, Cardassians have the benefit of an additional team above the usual limit, reflecting their martial ethos of domination though logistical advantage. This is just one example of how having important conversations early (and returning to them often) has helped keep the design for Star Trek: Into the Unknown on course.

On the Cosmere RPG, my role as a consulting designer has continued to evolve. While I was fairly involved with core design in the early days, as the team has grown, my responsibilities have shifted to focus on mentoring and design guidance more often than breaking new ground. So, while I drafted most of the Heroic Paths of Stormlight, I only handled a few of the ones in Mistborn, instead coordinating with a design team including Lydia Suen, Ross Leiser and others (including the continued guidance of mainstays like Stormlight lead designer Andrew Fischer). It’s a somewhat different skillset, but a valuable one for me to practice. And getting to see great designers like Lydia and Ross explore exciting, novel directions for heroic paths was really energizing. It’s always special when someone takes something you’ve made and elevates it, and I think people will be very pleased with what they’ll find when they venture into the mists of Scadrial!

The question here is: What can I do to proactively create continuity in the games I work on? How can I prepare future designers for success and ensure a smooth handoff where needed?

Taking Time to Savor Successes

Looking back at it, 2025 was undeniably a pretty good year for projects from 2024. Brotherwise Games delivered the Stormlight setting for the Cosmere RPG to wide acclaim. What’s more, I got to see the team really come into its own in a series of convention appearances, live plays, and more! Brotherwise has really put itself onto the stage as a major player in the RPG space, and I’m very proud of the small role I got to play in that as a consulting designer.

And in an unexpected but exciting turn, Star Trek: Into the Unknown was not just nominated for an Origins Award for miniatures games, but actually won! My design partner Michael Gernes had a hand in a past Origins win for Star Wars: Armada, but for me, this was a big first! And what’s more, despite global trade disruptions and other challenges, the game has found an enthusiastic audience who appreciates the depth of the thematic experience Michael and I set out to create. I’ve reflected on the way games form and encourage communities before, and I’m really pleased with the energy we’ve seen from the coalescing STIU Community.

Watching the successes, often from afar, has been slightly bittersweet. In 2025, I’ve prioritized getting stuff done. 2025 was the first year sinc 2020 where I considered returning to the convention scene, but I made a conscious decision not to push to get to a bunch of shows for self-promotion. I did this partly because of scheduling conflicts with a few big shows (I’d marked off possibly attending Adepticon and GenCon, but the dates just didn’t work), but also to reserve this time to work on new projects. I had a lot on my plate already, and I had a new game to design (more on that later).

I think this was the right call, but it was unquestionably a tradeoff, and I really felt that this year. Observing the public reception to games without needing to travel is more feasible than ever thanks to digital communications. But it’s not the same as running a session of an RPG in person at a convention or seeing people’s excitement at an organized event. These sorts of interactions with the game in the wild were just baked into the experience of working at FFG five years ago. For several years, I held off due to the pandemic and the time commitment of getting my freelance career started. But after several years of absence, I realize that I miss these moments more than I expected.

The question here is a paradox. I can’t solve it because there is no right answer, and I’ll need to try new things to find the right balance: How much time do I want to shift from making games to engaging with game communities outside my office? What kinds of involvement in community are most important to me?

Leaving Things in the Back of the Fridge

A beef shoulder from the Egyptian New Kingdom, courtesy the Met Collection. The oldest open-source image of food I could find. Unrelated to the topic, presumably.

As my schedule has gotten more cramped with projects, this blog has definitely languished. I’ve drafted a fair number of posts in the last year, but none of them have reached a state of readiness where I felt comfortable posting them. Looking back, I ask myself why this is, and I think there are a couple of reasons:

Some were topics that I felt petered out in the process of writing them. I tend to be a “discovery writer,” forming my thesis organically as I work and then editing the piece afterward. A few of my would-be posts began to feel hollow at this stage.

Others I struggled to bring up to a level of polish I felt comfortable publishing. And amidst deadlines and other commitments, it was often easier to leave them as drafts than put in the considerable energy required to carry them over the finish line.

Some sounded good in my head, but felt obvious on page. I don’t want to waste people’s time with articles that aren’t interesting.

The question here is practical: Have I already written something that applies to the topic? Is there anything in my blog drafts, my game drafts, or my prototype pile that I should revisit? Is any of it still fresh?

Next Year’s Meal Planning

“Okay, but this is all reheated 2024 leftovers!” I hear you say. “What was that you said about starting your own game company? About an exciting, new project? Also, the cooking metaphor has been on the stove way too long. Oh no, now you’ve got me doing it!”

All right, let’s discuss the other thing I’ve been doing.

In early 2025, I started a company to pursue my own game designs. Since April, I’ve spent a good chunk of my time working on two major projects for Wild Plum Games.

Why did I do this? Well, for two reasons. The first is that, in my time freelancing, I’ve realized that there are a couple of games that are important to me, but that no publisher is going to show up and just ask me to make. That’s fair. One of the reasons to be a publisher is to make the games you want to make. Secondly and more importantly, I’ve come to the conclusion that I want these games to exist not just as games over which I have creative control, but also as products I that I create on my own terms.

What’s the difference between designing a game and designing a product? Game design and product design are interconnected, but there are important distinctions between the two. If one thinks of game design as the work of crafting a game’s rules, product design is the work of deciding on the objects that those rules inhabit, from the rulebooks to the box to the components. It covers everything from choice of materials to choice of process to setting the recommended shelf price of the game. It’s hard in a different way than game design, because it’s work that really makes you put your values and your aspirations on the scale. I’ve made product design contributions before (Michael and I designed the maneuver tool for Star Trek: Into the Unknown, for instance), but I’ve never taken a lead role on product design. I want to do that now.

Of course, starting this work doesn’t mean I’m stopping my work on other projects. I’m still involved in Stonesaga as it releases to the public, the ongoing work on the Cosmere RPG, new expansions for Star Trek: Into the Unknown, and even a couple of hitherto unannounced freelance projects that I might be talking about this time next year.

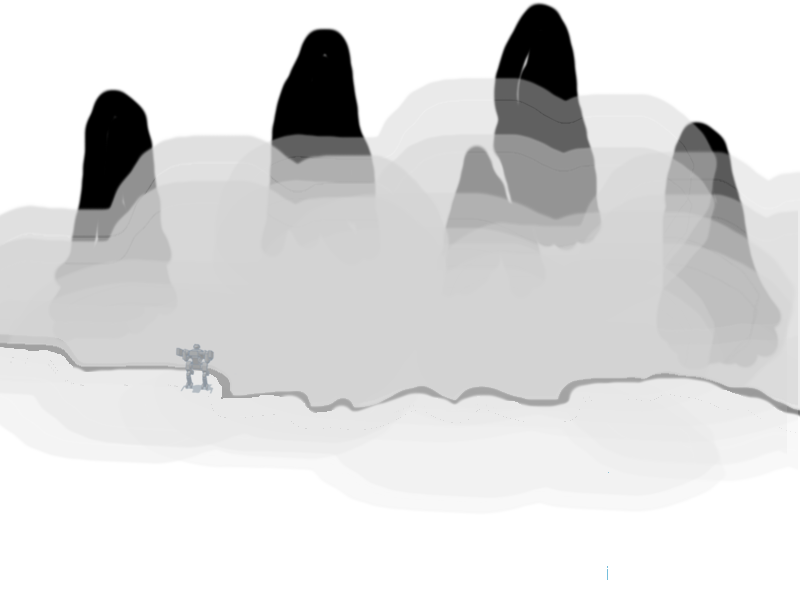

And what are these new projects that demand this endeavor? I’m going to leave a tantalizing hint again, but this time, you won’t have to wait a year to see it pay out…

Don’t worry, I’ve hired artists who can draw competently and even beautifully. But sometimes I can’t help but opening up TinkerCAD and PaintNET to spin out another Dubious Max Brooke Original.