Stonesaga: Going with the Flow

This is an expanded version of a designer diary posted on BGG. Hopefully folks find the extra commentary interesting!

Whether you’re designing a competitive 1-v-1 game, a cooperative story game, or a roleplaying game with a GM and players, one of the most crucial yet elusive parts of game design is finding your game’s ideal flow.

In broad terms, flow is the pacing of the game, the way in which one action runs into the next to form a cohesive and (hopefully) satisfying experience. In chess, the flow is a series of back-and-forth actions that cause the board state to progress. Each action has tactical ramifications, and in aggregate, all of the actions have strategic consequences that eventually lead to the game’s outcome. The fact that chess includes rules to prevent repeating board states indicates that each action changing the board meaningfully is important to the flow of chess. It isn’t enough that an action is tactically interesting, it must also contribute to the strategic progression of the game.

Flow(chart) of Priorities

Obviously, Stonesaga’s flow isn’t going to look much like that of chess. Stonesaga is cooperative, highly evocative rather than abstract, and grapples with very different themes and concepts from chess. But, like chess and a lot of other board games, Stonesaga does present a player with multiple needs at once and numerous ways to address them. Chess’ different needs are tactical (how to the most out of one move), strategic (how to progress the board state favorably over multiple moves), and interpersonal (how to learn about the opponent through the strategic progression), and the toolbox a player has to address them are the many different moves each piece can execute.

To understand Stonesaga, we need to begin by looking at what it encourages players to achieve during each game. Stonesaga’s competing needs can be mapped as follows.

Immediate needs include taking care of your own character’s basic requirements. This means gathering food and water to recover energy, finding shelter to ward off the elements, and making fire to protect yourself from the valley’s icy nights. Fulfilling these basic needs will usually consume at least some of your group’s energy.

Time pressures come in the form of activity (which increases each night, can trigger new events, and eventually end the game), unrest (which increases when you and your society are at odds), the behemoth, and goals you can only complete in your current game. These give you incentive to act on a more strategic level, avoiding problems or completing goals to progress toward the end of the game on your preferred terms.

Finally, curiosity and progress provide a third pillar of motivation to continue exploring the world, investigating omens around you, and crafting new items and structures that will persist into future Challenges, giving you a leg up in later games.

There are other ways one could break down these needs (such as with a hierarchical model), but just thinking about these three categories helps underscore why the choices in Stonesaga often become difficult. Do you want to make progress on a future accomplishment at cost to your current status? How do you manage the time pressure against your immediate needs while still learning more about the valley and its secrets? These are the questions that make for hard but interesting choices, reward players who consider their options carefully, and will ultimately make different players’ experiences quite varied based on what they chose to prioritize and how this shapes their society and world.

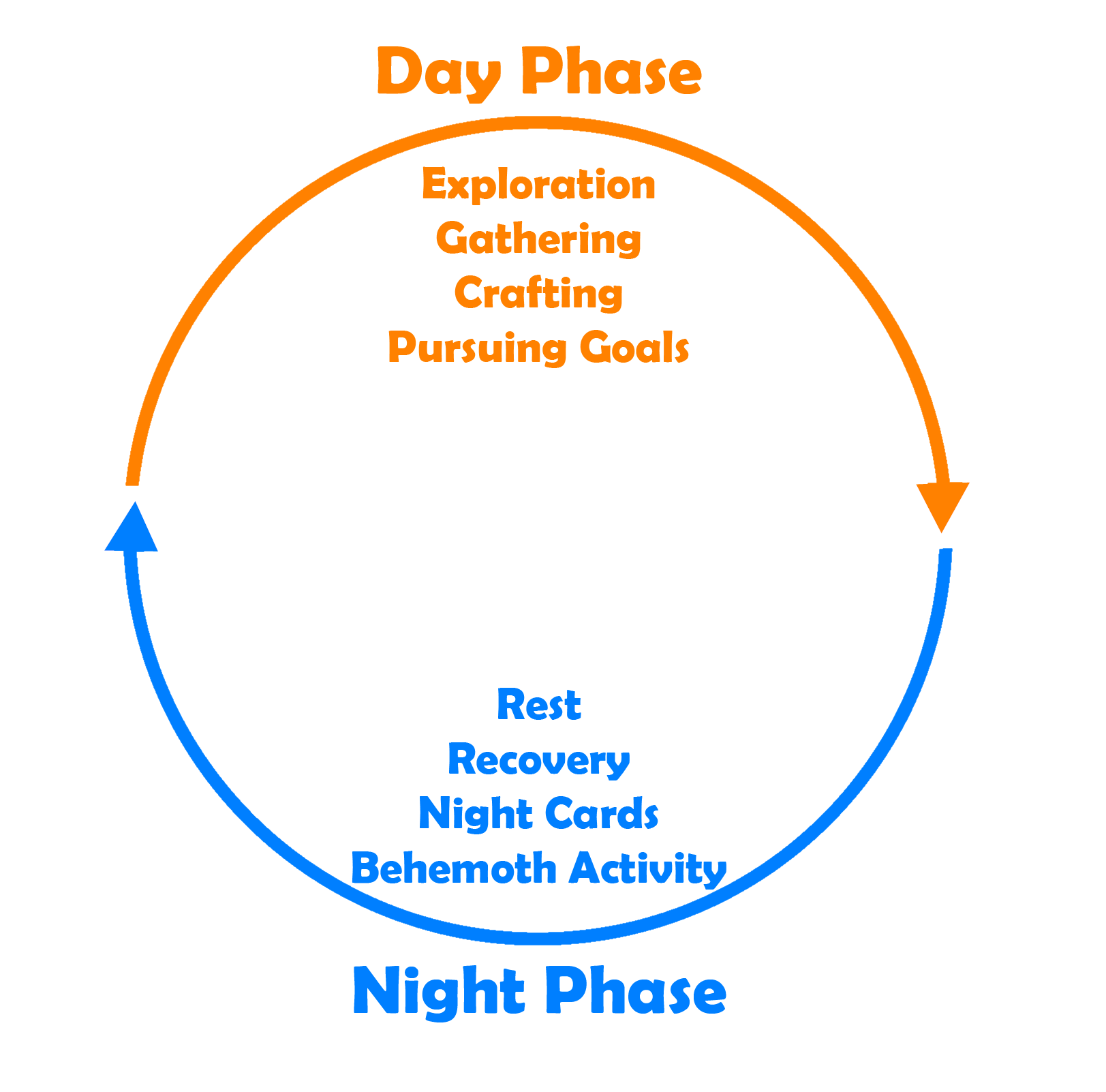

If immediate needs are basic upkeep, activity is the clock that keeps people moving toward their Goals, and curiosity is the force that draws people to step off the path to learn the game’s hidden secrets, the Day/Night cycle is the arena in which these motivations compete.

The Cycle of Play

Each game of Stonesaga (a Challenge) takes place over multiple Day and Night phases. Days are the character’s chance to act on the board by spending their energy, while nights both gives character a chance to recuperate and also toss new problems their way that reward proper preparations.

During each day, characters can take actions that contribute to filling one or more of these needs. Each action costs 1 or more Energy, and characters can take multiple actions per day so long as they can pay the energy costs.

Characters can explore the map to find new terrain features, which gives them a wider range of options for gathering resources. Some resources, like food and water, fulfill immediate needs. Others help complete Goals before the activity track ends the game. And still other resources are needed for crafting new items and structures.

However, it’s hard to fulfill all of these competing needs in a single day. This is where choices get interesting. Gathering water reliably provides 2 water for 1 energy at a water feature like a river or lake. But foraging and fishing, which cost 2 energy, can provide water if the character gets lucky, and might also provide other resources at the same time. Players must weigh the risk against the potential return of their action, as well as the options that are available in their current hex and nearby hexes they can reach in a few moves. Additionally, while gathering water is safe and reliable, foraging and fishing can provide insights into the valley’s secrets that the safer, lower-cost action can’t through investing omens or reading codex outcomes.

Every night, characters must face consequences of their decisions during the previous day. First, characters rest and recover energy. The more of their immediate needs they met, the more energy they will have available to use the next day. Further, meeting these needs helps characters recover from disease and injury, and generally prepares them better for the next day.

Characters must also draw a Night card each night (or possibly more than one, if they have spread out on the board). This Night card showcases the dangers of the valley: blizzard conditions, dangerous predators, and unexplained happenings can all befall the characters. Many of these cards have bonuses for making the right preparations, however. Clothes, shelter, fire, and other tools can be key to coming out of the night unscathed. The Night card also changes the omen and increases activity. This can trigger new events that might impose difficulties on the characters and pushes the Challenge further toward its inevitable conclusion.

Finally, once it is present, the behemoth acts at night, pursuing whatever agenda it may have in the valley. As the characters’ society grows to understand the behemoth better, the players may devise methods to minimize or even benefit from the disruption this massive creature can create. Many of the long-term projects characters can pursue over multiple Challenges, like the acquisition of lore and creation of items, can help make dealing with the behemoth easier or open up new options that did not previously exist. This is one of many ways the game rewards the pursuit of player curiosity, as there are more options to address the challenge the behemoth presents than that it might seem at first, but uncovering these options requires diving deep into the secret lore of the valley or inventing new technologies to circumvent problems the behemoth creates.

The Tug of War

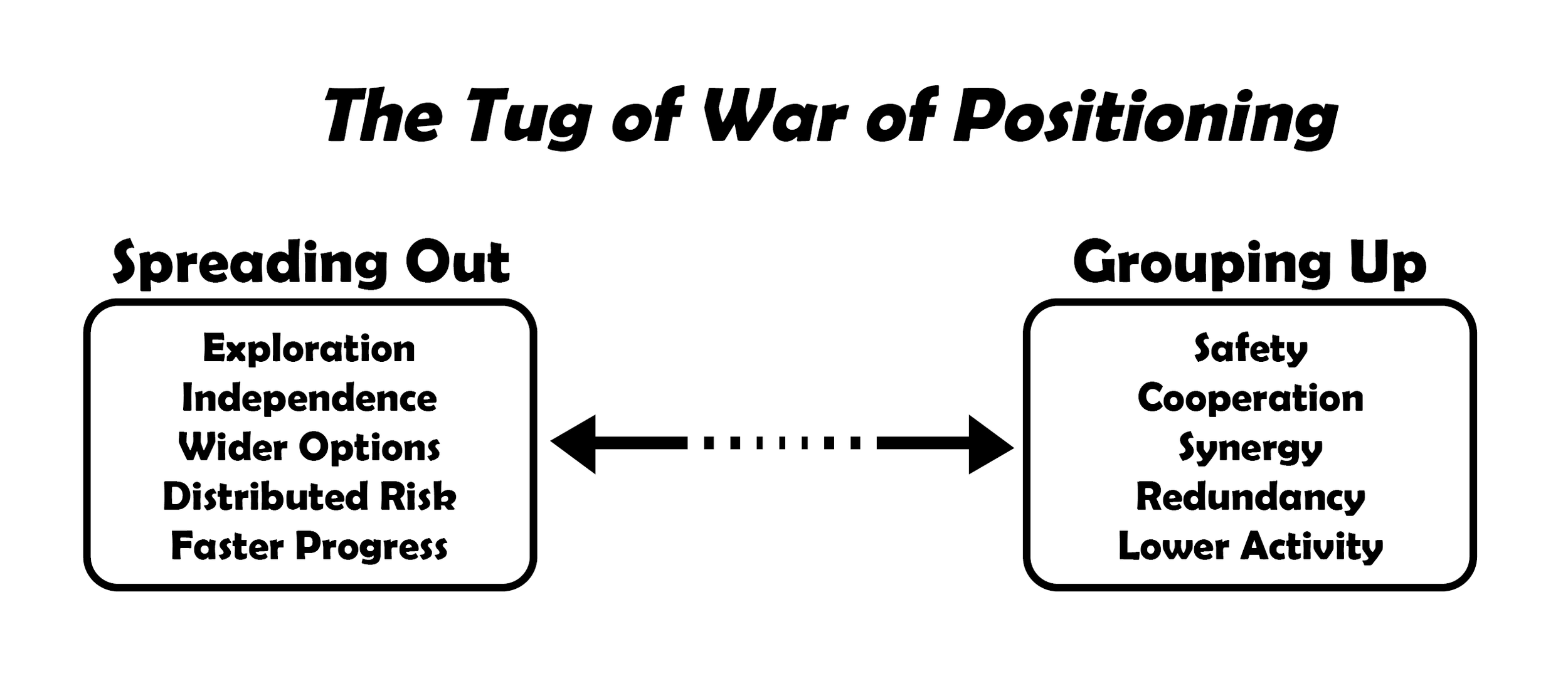

One other key element of Stonesaga’s flow of play is the competing incentives between clustering up in the same hex to cooperate and the desire to expand outward and discover many hexes.

Spreading out has some key benefits. It gives players a chance to find new things that help solve the group’s problems. It also fulfills a desire many players have to explore. It creates a wider net of option for the group, which can make acquiring specific resources and achieving particular Goals easier (or even make previously impossible Goals possible).

Further, it distributes risk, as each character is unlikely to be affected by the problems the others encounter as they explore and weather harsh nights. It also decreases the risk of failing to find key assets. If the group really needs a forest to harvest a particular resources, spreading out is far more likely to uncover that feature quickly.

However, there are also critical advantages to staying close together. Being in the same hex allows characters to share resources and use beneficial abilities on one another. It also lets characters share helpful assets like shelter and fire, meaning the group can dedicate less energy to fulfilling these basic needs for everyone.

It also provides lower activity increases, as fewer Night cards are drawn. While there is a chance all players will be subject to a particularly rough draw that affects everyone, the group will have more time to finish their Goals before the game ends if they end every Day phase clustered up.

A Work in Progress

Stonesaga’s flow of play hasn’t yet been perfected. While playing the Beta has made me feel very confident about the overall concept, the devil of such things is always in the details. The balance of activity rewards, Night card effects, density of features on terrain hexes, and activity tracks on Challenge cards are still under close evaluation. If you’ve had a chance to try out the Beta and have thoughts on the flow of the game and how to polish it even further, please leave us a feedback form about it or drop a message here. There’s still a lot we can all learn about Stonesaga as we move toward the best version of the game we can make together!